Absolutization

A multi-disciplinary account of the sources of dogma, repression and conflict

Now published by Equinox!

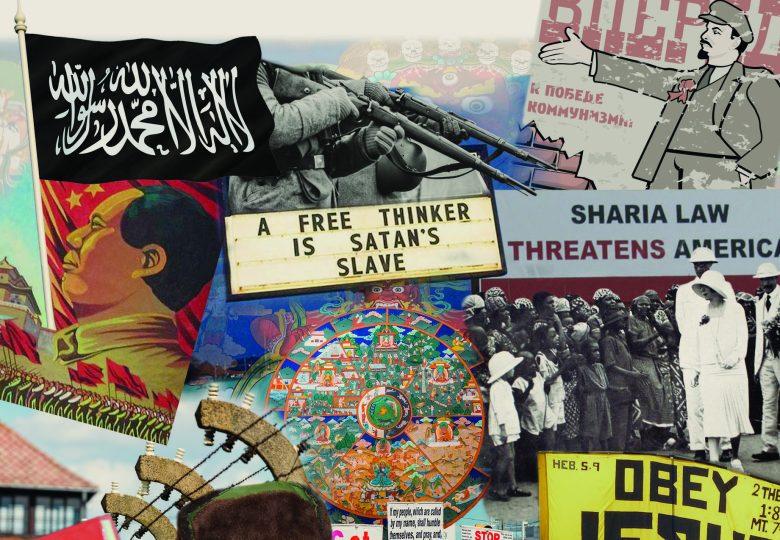

What do dogma, repression and conflict have in common? They all result from human judgement blocked from wider understanding by a false assumption of completeness. This book puts forward a theory of absolutization, bringing together a multi-disciplinary understanding of this central flaw in human judgement, and what we can do about it. This approach, drawing on Buddhist thought and practice, philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, embodied meaning and systems theory, offers a rigorous introduction to absolutization as the central problem addressed in Middle Way Philosophy, which is a synthetic approach developed by the author over more than twenty years in a series of books. It challenges disciplinary boundaries as well as offering a substantial framework for practical application.

This book is the first of the new Middle Way Philosophy series to be published by Equinox.

Read the Preface and Introduction of this book

Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figures

Acknowledgements

Foreword to the Middle Way Philosophy Series by Iain McGilchrist

Preface

Introduction

1. Early Buddhism

a. Mental Proliferation

b. Craving, Hatred and Delusion

c. The Absoluteness of Negations

d. Excluding the Options

2. Systems Theory

a. Reinforcing Feedback Loops

b. Assumed System Independence

c. Fragility

3. Embodied Meaning

a. Representationalism

b. The Denial of Embodiment

c. Discontinuity

d. Interpretation

4. Philosophy

a. Metaphysics

b. The Absoluteness of Deductive Logic

c. Foundationalism and Circularity

d. Infinite Rationalization of Experience

e. The Claim that Metaphysics is Inevitable

f. Inflation of Metaphysics and Logic

5. Psychology

a. Repression and conflict

b. Projection

c. Confirmation Bias

d. Substitution

e. Group binding

f. Archetypal Function

6. The Unity of Absolutizing Phenomena

a. The Blind Synthesist

b. Clarifying the Relationships

c. The Use of Synthesis

d. The Practical Arguments

7. Criteria for a Response: Practicality

a. What is Practicality?

b. Embodiment

c. Responsibility

d. Effectiveness

8. Criteria for a Response: Universal Aspiration

a. Top-down and Bottom-up Universality

b. Normativity

c. Systematicity

d. Universality across Groups

e. Universality across Space

f. Universality across Time

9. Criteria for a Response: Judgement Focus

a. Judgement as the Cutting Edge 201

b. Diversions from Judgement Focus

10. Criteria for a Response: Error Focus

a. Falsification and Error Focus

b. Refining Shadow Avoidance

c. Emotionally Positive Context

Conclusion: Criteria for the Middle Way

Appendix: Table of the 23 Dimensions of Absolutization

The Old and New Middle Way Philosophy Series

Bibliography

Absolutization: Summary

Preface

This book offers an inter-disciplinary perspective on what is ‘extreme’, which has developed out of 20 years of work now entering its third phase of expression. Its synthesis is tested by critical scrutiny, with evidential support for empirical claims. It is framed by an overall practical purpose.

Introduction

Absolutization is, broadly speaking, the belief that we have the whole story. It encompasses dogma, bias, fallacy, metaphysics, repression, certainty, projection and addiction, and I’m aiming to show how these phenomena are linked. Finding what these have in common allows us to address them more effectively together, when academic specialists have tended instead to play the blind men and the elephant. This book first connects 23 features of absolutization with 5 different starting point disciplinary areas. It then identifies 4 criteria for any effective response to absolutization.

1. Early Buddhism

a. Mental Proliferation

Mental proliferation consists of energy continually directed down the same mental and neural channels to produce repetitive thoughts and feelings. The energy applied is continually trying to remove the same obstacles to a goal, but the obstacle is part of a complex system and is not so easily removed. This proliferation is the prapañca mentioned by the Buddha, and can also be directly experienced in mindfulness practice. It connects desire and belief in maladapted patterns.

b Craving, Hatred and Delusion

Buddhism identifies the interdependence both between craving and hatred (which is frustrated craving), and between craving and delusion, in the extremes avoided by the Middle Way. This interdependence is confirmed by neuroscientific evidence, but defies the weight of assumption in Western thought.

c. The Absoluteness of Negations

The negation (in the sense of affirmation of the opposite) of an absolute belief is equally absolute, and this needs to be distinguished from a mere failure to affirm it. This point is the basis of the Middle Way in Buddhism, and can also be supported by neuroscientific and psychological evidence of the interdependence of craving with fear in representations that support both. This is also the basis of the link between dualism and absolutization.

d. Excluding the Options

Dualism excludes third options from consideration by restricting the framing of our judgement. The Buddhist Middle Way helps to avoid exclusion of options, but its traditional framing of the extremes to be avoided also continues to exclude options further. Greater optionality can resolve conflicts and enable adaptation, and can be applied spatially as well as conceptually. ‘Excluding the options’ is an established fallacy in critical thinking, but it involves taking dualistic framing for granted rather than a logical error.

2. Systems Theory

a. Reinforcing Feedback Loops

Reinforcing feedback loops, whereby organisms maintain and reproduce themselves in a self-replicating process, are a background feature of all systems. However, in the human case, the capacity for imagination adds a further capacity for balancing adaptability, that can then in turn be hijacked by more specific reinforcing feedback loops of belief. These reinforcing feedback loops appear as mental proliferation, and are prone to dangerous competitive escalation. This provides a crucial standpoint for understanding absolutization.

b. Assumed System Independence

Absolutization involves the assumption of the independence of an isolated cognitive system, whose representations can be considered apart from awareness of the psychological and neural process of their development. Systems theory offers no evidence of any such independent system being possible, and neuroscience gives evidence of how this assumed isolation operates so as to continually delude us.

c. Fragility

Fragility is the tendency of a system to remain stable only up to a ‘tipping point’, when the effects of its reinforcing feedback loops become incompatible with the environment. Absolutized beliefs drive human actions to such tipping points, after which the beliefs dramatically ‘flip’ to their opposites, as can be seen both in psychosis and in dramatic religious conversion. In the human system, absolutized beliefs are fragile because of a lack of antifragility or resilience – resilience which is experienced as grounded confidence and comes from testing against a breadth of experience.

3. Embodied Meaning

a. Representationalism

The development of embodied meaning theory, which shows meaning to be based on associative neural connection in response to experience, gives a context for understanding the limitations of representationalism. Representationalism assumes that meaning consists in the relationship between propositions and the actual or potential ‘reality’ that they describe. Absolutization assumes representationalism because its propositional claims as a whole are entirely ‘semantic’ and deny the variation of meaning with experience.

b. The Denial of Embodiment

The application of representationalism is combined with a more general denial of most of our embodied experience through the over-dominance of the left hemisphere perspective. This denial takes the form of the substitution of a disembodied shortcut for a more adequate process based on wider experience, encouraged by cultural entrenchment. This chapter briefly discusses 12 forms of this denial of embodiment.

c. Discontinuity

Discontinuity in space, time and conceptual space is a feature of absolutization due to the restriction of options in space. This is maintained by the over-dominance of left hemisphere sequencing over right hemisphere sustained attention, and makes us ignore the continuity of all organic processes. Although discontinuity is needed for practical judgement, absolutization takes this discontinuity out of that practical context.

d. Interpretation

Embodiment provides a wider context to help us distinguish whether statements that are apparently absolute in content are psychologically absolutizing. The presence of conditionality, practicality or a focus on meaning all provide contextual indications of non-absolutizing. Individual words or symbols also cannot be absolute by themselves unless they represent a belief. Nevertheless, absolutization can in practice be identified quite clearly in many contexts.

4. Philosophy

a. Metaphysics

Metaphysics is equivalent to absolutization because it involves claims about reality inaccessible to experience, so is discontinuous and dogmatic. Sceptical argument and philosophy of science offer tools that can help make some impression on it. Heidegger’s failed attempt to save it involved disguised sceptical argument. Merely philosophical arguments against it in logical positivism and postmodernism have failed, due to their lack of any systemic, embodied, or practical perspective.

b. The Absoluteness of Deductive Logic

Absolute deductive logic is believed in absolutizing thought to link together metaphysical claims in chains of certainty. Such logic was shown by Hume to be uninformative about the world. It can instead only be used critically to show inconsistency, whilst induction allows incremental justification of beliefs. Changing logical systems does not help with this, as it is the absoluteness of our interpretation of logic that is the problem. Absolutization tends to make us over-inflate logic’s usefulness in claims about fallacies, rationality or ‘reasons’ in the world.

c. Foundationalism and Circularity

In the absence of any justification for metaphysical claims in experience, metaphysical thinking employs foundationalism (dogmatic assertion of the truth of starting points). When challenged, it then uses circular and ad hoc arguments to substitute for experiential justification. Circular argument proliferates and creates reinforcing feedback loops. By projection, rationalists often accuse others of the very circularity they demonstrate themselves.

d. Infinite Rationalization of Experience

The philosophical content of metaphysical beliefs can be linked to the psychological defences of absolutization by the way that infinite scope allows endless rationalization. This is exemplified in ad hoc argument, and can be supported by cognitive dissonance theory. Its further implication is that metaphysical beliefs are impervious to observation, and thus also to probability.

e. The Claim that Metaphysics is Inevitable

The claim that metaphysics is inevitable depends on the complete abstraction of metaphysical claims from the embodied context of them being held by a person. We do constantly make background assumptions, but these can’t be described as beliefs until they become practically relevant in some way (though not necessarily explicit), when we can distinguish absolute from provisional ways of holding them. Absolutization is a problem because it is practically relevant, but most alleged inevitable background metaphysical beliefs are not.

f. Inflation of Metaphysics and Logic

Both metaphysics and absolute deductive logic are also over-estimated through inflation, being used as shortcut substitutes for more complex experiential phenomena. ‘Metaphysics’ substitutes for profundity of meaning in religious experience and art, whilst ‘truth’ and ‘knowledge’ substitute for incrementally justified belief in science and education. The relativisation of these terms, on the other hand, robs us of minatory ways of referring to absolutes. Deductive logic is likewise inflated, to explain fallacious thinking that lacks justification due to absolutization of assumptions.

5. Psychology

a. Repression and Conflict

The insight of psychoanalysis is the recognition of conflict between different parts of our psyches that try to repress each other. This basic model, stripped of unnecessary elaborations, can also be supported by neuroscience. Conflict occurs between sets of associated desires and beliefs, emerging at different times, but each using absolutization to maintain its position over the others. This model can also be applied to socio-political conflict, which is between the desires and beliefs that are dominant within individuals at a particular time.

b. Projection

Projection, as distinguishable from normal features of perception, occurs when we take a particular meaningful feature of an object to be its only relevant feature. We take this feature to be the ‘real’ or essential feature of the object and thus have a metaphysical view that excludes alternatives, with all the other dimensions of absolutization. Such projection can also be reversed into an equally deluded opposite when we assume that that feature is instead totally absent from the object.

c. Confirmation Bias

‘Confirmation bias’ is a broad term that covers lots of other biases, all of which refer to our tendency to interpret new information only in terms of existing beliefs. Biases involve the substitution of fast processing for slow. These are absolutizations at the point where alternatives become relevant, but we either remain deceived by the bias, or react by taking the opposite view that our biased view is completely false. Bias at this point is indistinguishable from fallacy.

d. Substitution

Substitution is typical of absolutization, consisting of the use of an easier process instead of a harder one. In cognitive psychology this is often taken to involve substituting a simpler deductive process for a more complex one. However, once complex deductive processes have been made easier through practice, they start to substitute for more complex inductive or experiential investigations. Even those trained in science may switch to deduction when outside their area of comfort.

e. Group Binding

Absolutization is a shortcut for binding groups and exerting power, by creating unquestionable shared belief on which group identity is dependent. Four recognized biases provide evidence for group binding: the ingroup-outgroup bias, groupthink, social proof and false consensus. A reaction against group binding may produce negative absolutization for a counter-group or for individualism. This is not an inevitable feature of group relationships, which can instead be based on our experience of solidarity, and even the use of power can be made conditional.

f. Archetypal Function

The concepts of infinite openness that are often used in absolutizing beliefs can also have a beneficial archetypal function. This function depends on the provisionality of the context in which such concepts are used, and works by creating associations between archetypal symbols and experiences that involve moving beyond a limited identification (such as aesthetic, moral or religious experiences). This function means that religious traditions should not be reductively associated with absolutization, but rather credited as having mixed effects in need of critical differentiation.

6. The Unity of Absolutizing Phenomena

a. The Blind Synthesist

Objections to the very idea of synthesising the different dimensions of absolutization from different disciplines may often come from a bias of over-specialisation. My alternative is not to claim a total view, but to recognise my own partial view whilst synthesising a variety of other views that are each partial – not primarily in terms of their content, but in terms of their framing.

b. Clarifying the Relationships

The dimensions of absolutization are not deductively equivalent a priori, but are closely related elements of the same system that become evident in particular conditions. From the diachronic standpoint needed to relate these different conditions of emergence over time from different standpoints, though, the unity of the dimensions is just as evident as that of most theoretical constructs in science.

c. The Use of Synthesis

Synthesis combines understanding in different schematic and metaphorical frameworks, which is a necessary condition for creative thinking. The justification of a synthetic view, however arrived at, involves a process of combining meaning and dialectically sifting belief. Such justification becomes greater the more it can be used to explain a variety of phenomena. The approach to combining perspectives in this book is concatenative, meaning that the addition of more synthesised perspectives adds to the level of justification.

d. The Practical Arguments

The dimensions of absolutization also need to be understood in relation to each other for practical purposes, meaning to help us progress towards long-term provisional goals that involve reducing absolutization. The need to address neglected dimensions of absolutization will be an aspect of my discussion of the four criteria for the Middle Way in the rest of this book. In particular, the failure to adequately address practical judgement in the world in large sections of academia can be associated with the entrenched influence of representationalism, separated from the other dimensions of absolutization.

7. Criteria for a Response: Practicality

a. What is Practicality?

Practicality is a strength of Buddhist tradition and involves interconnected techniques, acknowledging embodiment and developing responsibility and effectiveness. Theory at a high level of generality can also be practical as long as it avoids absolutizing shortcuts. Restrictions in scope need to be provisional if they are not to detract from practicality, but academic specialization is often not seen provisionally. ‘Pragmatic’ philosophy has also lacked practicality, because of its representationalism, not distinguishing the meaning of ‘truth’ from belief in it.

b. Embodiment

To make our beliefs practical, our theories as well as our more immediate practical beliefs need to be scaled to human embodiment. This means adapting to our limited perspective by avoiding metaphysics – even though ‘saints’ may manage to maintain embodied beliefs in spite of the presence of metaphysical beliefs. It also means adapting to our limited capacities by avoiding both freewill (total responsibility) and determinism (zero responsibility) assumptions.

c. Responsibility

Responsibility can have both a ‘felt’ sense and a sense we are socially held to, but the former is needed (separated from law) as an aspect of our practical response to absolutization. Felt responsibility integrates and motivates, though it may need prompting by reminders. It applies not only to values, but to our interpretations of facts, the definitions of terms and our mental states. In all these ways we can avoid absolutizing dualities by developing felt responsibility.

d. Effectiveness

Absolutization may temporarily boost the intensity of our goal-directed action, but even that intensity is reduced by conflict. The more complex our activity the more direction rather than intensity becomes important, and the more absolutization interferes with that directionality, especially over time. In response, we need to develop genuine confidence, which arises from organic practice in embodied judgements in a varied environment, not from absolutized belief.

8. Criteria for a Response: Universal Aspiration

a. Top-down and Bottom-up Universality

Top-down universality, which creates absolutization, involves generalization from part to whole, followed by deduction from beliefs about the whole. Bottom-up universality, on the other hand, makes use of meaningful concepts for universality to inspire a search for a more complete view. The latter is needed to move practical beliefs beyond parochialism.

b. Normativity

Normative expectations of what we ought to do are needed to address the absolutizing tendencies either to rely on the fact-value distinction, or to idealized normativity. Normativity is not ‘queer’, but an aspect of embodied practice that needs a motivating prompt from archetypal universals to help us make more provisional judgements. When motivated it stretches what we can do slightly beyond our existing identifications.

c. Systematicity

Systems thinking also prompts a universal aspiration to motivate us to move from linear to complex thinking, whether on boundaries, categories, causal relationships or goals, which form the basis of our factual understanding of a situation. This is reflected in the development of ‘ideal’ conceptual models as an aspect of problem-solving in soft systems methodology.

d. Universality across Groups

Universality across groups does not consist in similarity of moral rules, but in similarities in the ways absolutization can be overcome. These appear to be very similar across human populations. To access shared provisionality across group divisions, mediation processes promote mutual recognition of shared needs and conditions. Genuine universality thus comes from addressing psychological conditions rather than finding shared top-down prescriptions.

e. Universality across Space

Universality across space involves stretching from an embodied experience of space towards an idealized (universal) conception of it, also avoiding a parochial limitation of space. Our identification with spaces is deeply rooted, but requires stretch to address world-scale problems. The Middle Way as a metaphor stretches our bodily experience of moving through embodied space towards a goal in conceptual space.

f. Universality across Time

Universality over time involves stretching our awareness from the present over time, without that awareness being substituted by absolutized conceptual beliefs about it. Such beliefs can be represented by temporal biases that absolutize past, present or future over the other times. Such biases are not removed by reactions that completely deny the relevance of the other time, but require an integrative approach, extending our awareness of responsibility rather than imposing it.

9. Criteria for a Response: Judgement Focus

a. Judgement as the Cutting Edge

Judgement is the cutting edge of our interaction with the world. Whether it is absolute or provisional determines the crucial how of justified judgement. Judgement focus helps us recognise our experience of building up responsibility for judgement through awareness of options maintained over time. It avoids both the opposed attractions of freewill and determinism, whereby we have total or zero responsibility for our judgements a priori.

b. Diversions from Judgement Focus

Whilst the most obvious diversions from judgement focus are blatantly metaphysical, the nearer and more practically damaging distractors involve representationalist assumptions introduced into investigations that appear to be addressing absolutization in some respect. The spurious claim to be focusing on facts without values undermines the value of academic work in, for instance, Buddhist Studies, cognitive psychology, and moral philosophy, by entrenching the omission of crucial elements of the context in each case.

10. Criteria for a Response: Error Focus

a. Falsification and Error Focus

Error focus is a more effective approach than positive focus for avoiding confirmation bias as a dimension of absolutization. It suggests that we make incremental progress towards objectivity, not by eliminating absolutely false claims, but by identifying absolutizations as the erroneous how of judgement. This is reliably but not absolutely available to us from reflection on individual experience of past judgements, and applies equally to all kinds of judgement – individual or social, scientific or moral.

b. Refining Shadow Avoidance

A focus on avoiding error is an avoidance of evil in the sense of threats from absolutized human judgement, that we have learned to recognize in ‘evil’ characteristics. This is the most practically important part of our response to the shadow, which also includes ‘natural’ evils. It is better targeted than the identification of evil as sociopathic character, which involves the projection of one variable feature as necessary to a character as a whole.

c. Emotionally Positive Context

Although logical negativity is conventional and reversible, the idea of error may still have emotionally negative associations for us. These can be put in a wider positive frame by a growth mindset that puts error in the context of wider success, so are not a sufficient argument against error focus. The development of a growth mindset may be aided by mindfulness, imagination and critical thinking practices.

Conclusion

A connected response of this kind is needed to absolutization to avoid seeding new absolutizations whenever we respond to existing ones. Any such connected response is the Middle Way, because it avoids either acceptance or rejection of idealized beliefs in our response. The four criteria give general philosophical parameters for identifying the Middle Way, but do not give guidance for practising it. The five principles of the Middle Way that are the subject of the next book in this series – scepticism, provisionality, incrementality, agnosticism and integration – provide a basis for practice that addresses the overall conditions created by absolutization.