The Five Principles of Middle Way Philosophy

Living experientially in a world of uncertainty

Now published in paperback, hardback and ebook (see publisher’s website).

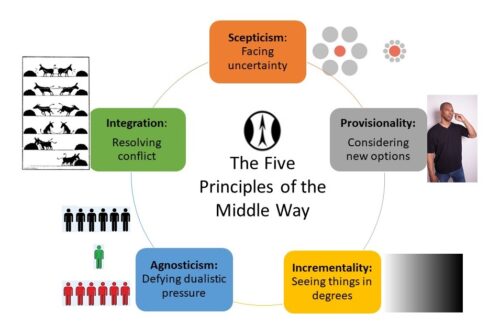

This second book in the ‘Middle Way Philosophy’ series develops five general principles that are distinctive to the universal Middle Way as a practical response to absolutization. These begin with the consistent acknowledgement of human uncertainty (scepticism), and follow through with openness to alternative possibilities (provisionality), the importance of judging things as a matter of degree (incrementality), the clear rejection of polarised absolute claims (agnosticism) and the cultivation of cognitive and emotional states that will help us resolve conflict (integration). These are discussed not only in theory, but with links to the wide range of established human practices that can help us to follow them. Like all of Robert M. Ellis’s work, this book is highly inter-disciplinary, drawing on philosophical argument, psychological models and values that prioritize practical application.

Read the Introduction to this book

Chapter Summary

Introduction

This book builds on the previous volume, ‘Absolutization’ by presenting the practical response of the Middle Way to overcome absolutization. The Middle Way is not a compromise, but a navigation between opposing absolutes that is neither absolutist nor relativist. The five principles of scepticism, provisionality, incrementality, agnosticism, and integration are outlined. All of the five principles follow the four criteria for a response to absolutization found in the later part of ‘Absolutization’ – practicality, universal aspiration, judgement focus and error focus – but they offer a more practical focus.

1. Scepticism

a. Uncertainty, ‘Knowledge’ and Sceptical Argument

Scepticism is a practical recognition of uncertainty, which should not be confused with falsehood. Its arguments show formal propositional knowledge to be impossible, because we have no access to truth or complete justification. These arguments are that empirical justification is unreliable, rational justification is subject to infinite regression, and all knowledge claims depend on mistaken disembodied assumptions about meaning.

b. Scepticism is not Negative

Scepticism is frequently misunderstood as negative in motive or application, but arguments about uncertainty in no way require falsehood. Assumptions that they do involve an appeal to ignorance, and perhaps the unhelpful application of helpful principles within empirical judgement (such as Ockham’s Razor or Russell’s Teapot) to absolute claims. We slip easily into assuming falsehood from uncertainty, because the physiologically entrenched meaning of the dualistic framework is maintained in mere negation. Challenging that framework requires the practice of agnosticism as well as provisionality and integration.

c. Scepticism is not Impractical

The idea that scepticism must be impractical is due to confusing the merely meaningful possibilities raised by sceptical argument with recommendations for belief. Sceptical argument interpreted more helpfully is highly practical, supporting embodied confidence rather than certainty. To maintain that benefit we should not weaken the sense of ‘certainty’. Scepticism supports the development of felt rather than absolute responsibility, and greater effectiveness due to reduced conflict.

d. Scepticism, Embodiment and Meaningfulness

Sceptical arguments draw attention to our embodied limitations, and embodied awareness can also help us adapt to those limitations through the contextualization offered by mindfulness. Scepticism can cut through the dogmatic philosophies of mind that assume a separate observing mind even when they are supposedly ‘physicalist’. Embodied meaningfulness, developed from infancy, is also the basis of the confidence required to stop sceptical argument being used in alienating ways.

e. Scepticism is not Selective

Scepticism must be unselective to operate as such, but the reverse assumption that it must be selective has operated in much philosophy, theology, politics and ordinary life. Selective scepticism is the effect of confirmation bias, but this should be addressed through an expectation of even-handedness in practice rather than entrenched through institutionalized acceptance. Sceptical argument used for the Middle Way is not itself selective, and does not ‘paradoxically’ exempt itself from uncertainty, because it is not externalized or representational.

f. Scepticism does not Threaten Meaning

Scepticism is wrongly accused of threatening meaning. The accusation that it undermines absolute religious beliefs that are a source of meaningfulness depends on the confusion of profound religious experience with absolute beliefs that have no necessary relationship with it. Wittgenstein’s accusation that scepticism is meaningless depends on the questionable assumptions that scepticism makes absolute claims, that belief precedes meaning, and that meaning is judged by communicative function rather than being an experience.

g. Scepticism applies to Values and Facts

Scepticism challenges the assumption of an absolute distinction between facts and values, given that both kinds of belief are not denied but incrementally justified (even if asymptotically for some obvious factual statements). Both factual and value claims depend on human goals and assumed states of affairs that depend on those goals. The particularity of values does not make them ‘subjective’. Moral beliefs, like factual ones, become more justified as they are more integrated.

2. Provisionality

a. Optionality and Adaptiveness

Provisionality helps us positively look beyond absolutization by having alternative options available. These options may or may not be consciously considered, but are possible channels for our desires. Having greater optionality enables adaptivity, in the sense of helping us meet a variety of needs in changing and unpredictable conditions. These further options can also be seen as a range of weak links in our neural networks. Provisionality is compatible with decisiveness, because time-framing is one of the conditions we need to address (considering the maximum range of options) in judgement.

b. Complexity and Antifragility

Complexity cannot be an ontological feature, but rather requires provisionality, because our perspective is part of the complexity of the system. Developing optionality helps us to address the conditions of system complexity, but we need to beware merely abstract academic acknowledgements of uncertainty without it. In practice, optionality can produce antifragility by strengthening system resilience.

c. Slowness

Slower and more energy-sapping processing is needed for more complex provisional judgements, when compared to faster automatized ones. Bias is maintained by fast absolutized judgement when slower ones could be used. However, sometimes speed is also required by conditions, so provisionality consists in slowing down judgement when conditions allow, to consider options and improve it later when faster judgement is needed.

d. Synthesis

Synthesis can occur at the meaning level as imaginative connection, and at the belief level as new theorization from the dialectical integration of previously opposing beliefs. Synthesis of beliefs depends on provisionality in which new possibilities are considered, motivated by a point of frustration with conflict. Practice of the five principles is needed to prevent synthesis becoming dogmatic, but it is still required for creative thought. Analysis, by contrast, depends on and reinforces previous assumptions, and has been over-emphasized as a result of over-specialization in the modern economy and in academia.

e. Suppression

Suppression is highly necessary to provisionality, because without the ability to temporarily direct our attention away from absolutizing distractions, we would remain stuck in them. Suppression allows awareness to continue, in contrast to repression which tries to eliminate an object of conflict. Suppression is recognized in psychology as a ‘mature defence’, which may also take the forms of sublimation, altruism, anticipation, or humour.

f. Probabilizing

Estimating probability, even if it cannot be very precisely determined, is an important aspect of provisionality practice. It is an estimate of justification rather than of a relationship to ‘reality’, and the process of making that estimation is more important than the results, because it helps us avoid absolutizing. We need to take very small and very large probabilities seriously, and even recognizing the distinction between asymptotic probability and certainty is still of general practical value. We can also probabilize value claims by considering the probability of the prescribed desires being fulfilled in an integrated form.

g. Weighing up

Weighing up is the final process of making practical judgements when these are required, a process that can be contrasted with that of merely deducing our conclusion. The process of weighing up involves determining comparative justification through both ‘positive’ elements that do involve reasoning (comparing options with criteria and with evidence) and ‘negative’ elements that determine the range of conditions considered by contextualizing beyond absolute assumptions. Deductions are often less important because are only about distinctions we identify with rather than practical outcomes.

3. Incrementality

a. Systemic Continuity

Incrementality is the practice of conceptualizing the qualities of all objects and events as a matter of degree rather than as discontinuous absolutes, aiding our continuing attention rather than shortcut absolutization. This gets us closer to a systemic view of objects that is not just left-hemisphere formatted. In practice this needs to be done in moments of reflection.

b. Tipping Points

Tipping points are rapid changes in systems that should not be confused with conceptually imposed discontinuity. Changes in systems take time, which is why attempts to force a conceptual vision without addressing all the conditions backfire. Genuine change in systems requires change in all the sub-systems, but we often fallaciously attribute a change only to its most immediate and evident cause. We adopt discontinuous social conventions and substitute these for gradual processes, or assume total change has occurred when previous conditions still have an influence.

c. Practical Discontinuity

Practical discontinuity is a requirement for acting in the world, which is necessary to our embodiment. This also means there are necessary social discontinuities such as the law. These practical discontinuities need to be carefully distinguished from ontological discontinuities. Practical discontinuities can be judged better or worse according to how far absolutizations were avoided up to the point of judgement, and this creates the basis of Middle Way ethics.

d. Continuity of Persons

Applying incrementality to persons means that we need to treat our descriptors of the qualities or categorizations of persons as a matter of degree rather than as absolute or essential, aiding provisionality. This applies to ourselves as well, offering a helpful interpretation of the Buddhist doctrine of ‘no self’. It can be applied in an array of ethical issues, for instance incrementalizing the absolute boundaries of personhood used in the abortion debate. This does not threaten respect for persons, which is dependent on how we judge our responses to others rather than essentialist beliefs about them.

e. Continuity of Time

The discontinuity of time depends on the differing way that our left hemisphere merely sequences, whilst the right experiences time passing. Applying incrementality to time prevents us fixating on one of the three times to the exclusion of others, and thus enables us to identify with our desires at different times. Temporal biases show the differing forms that this absolutization of time can take, with any view of an object having a temporal dimension. We need to shift from abstract beliefs about time to focusing on how we make judgements in time.

f. Continuity of Space

Our sense of the continuity of space is dependent on that of time, and also interacts with conceptual models of lines in space. We can recognize the incrementality of a boundary in physical space dependent on concepts, and also of conceptual boundaries modelled on physical space. We need provisional boundaries in practice, but these can be optimized by contextualizing our spatial assumptions. The Middle Way itself is also modelled in spatial terms, but has no absolute defined boundaries.

g. Continuity of Training

Training and learning are subject to tipping points (which create psychological stages) but are nevertheless continuous, and consistently recognizing this is a crucial practice. This means avoiding the expectation of instantaneous change, and cultivating a growth mindset in which failure is incrementalized and contextualized. On the other hand, specific achievements in learning in a given field also do not confer absolute authority in it.

4. Agnosticism

a. Wary as Serpents

We can find both non-absolutizing and absolutizing view in unexpected places, but the latter particularly requires us to be on our guard. Agnosticism is the practically necessary defensiveness involved in refusing to yield to pressure on both sides from polarized absolutizing groups. It also involves wariness to a whole set of absolutist dirty tricks against agnosticism, that try to make absolutism seem unavoidable. These include weakened accounts of agnosticism, appropriation of it, lumping into the opposing view, slipping even-handed positions into negative ones, and creating unholy alliances against it.

b. Even-handedness

Agnosticism is the practice of critical metaphysics, which needs to be even-handed in ways that previous criticism has often not been. This means an even-handed avoidance of absolutizations prior to any empirical investigation, not necessarily a ‘middle’ position in other respects. Views presented as ‘middle’ can still be metaphysically framed, or wrongly present moderation as necessarily correct. An even-handed assessment of empirical evidence can still incline us strongly to one side, but we still need to avoid even a leaning towards one side of a metaphysical debate, as this validates the metaphysical framework.

c. Strong, not weak, agnosticism

Contrary to the philosophical assumptions that dominate, ‘strong’ agnosticism (facing up to the state of not knowing) is far more provisional than ‘weak’ agnosticism (not knowing yet, perhaps in future). If the ‘knowing’ of weak agnosticism were to actually occur it would require massive absolute assumptions that the strong agnostic avoids through greater decisiveness. An analogy with addiction may make this clearer. This topsy-turvy cultural attitude to agnosticism results from a widespread obsession with discontinuous ‘knowledge’, and has so far prevented agnosticism being applied to all the other issues (beyond God’s existence) where it needs to be applied.

d. Awareness of Appropriation and Lumping

Appropriation defends against the Middle Way by assuming it to be part of a favoured absolutized belief, whilst lumping rejects the Middle Way by assuming it is part of a rejected absolutized belief. This can be done in either case by defining the Middle Way in absolutized terms, by applying the Middle Way in an absolutized way, by seeing the Middle Way as an aspect of an absolutized view, by substituting an absolutized view for a Middle Way view, or by seeing an absolutized view as an aspect of the Middle Way. This is problematic and requires wariness only because it obscures the Middle Way and results in further absolutization. Appropriation and lumping can also be used in service of the Middle Way.

e. Awareness of Sceptical Slippage

Sceptical slippage is the tendency to interpret uncertainty or agnosticism as grounds for denial, when it actually offers no more grounds for denial than for positive assertion. This occurs because a more troublesome two-shift process is needed to reach an agnostic approach, because of the pressure of group biases, and because of the culturally transmitted ontological obsession. Sceptical slippage results in flips substituting for reforms, failed revolutions, and fissiparousness in reform movements.

f. Awareness of Unholy Alliances

Unholy alliances consist of normally opposed absolutizing opposites uniting in opposition to the Middle Way, so as to defend the wider framing for their opposition. This can happen at political or at individual levels. Normally opposed individuals or sub-personalities may unite to reject the Middle Way by caricaturing it as conventionally middle, as indecisive, or as representing a rejected outgroup (as the normally opposed are temporarily welcomed into the ingroup).

g. Agnosticism and Psychological Development

Agnosticism requires a two-step process and thus seems to require the capacities of the fifth stage of development in Robert Kegan’s scheme. However, judgements do not always match capacities precisely, so this does not justify esotericism or an unqualified power hierarchy. Agnosticism also needs to be applied at the micro-level (between opposing shortcuts when transitioning between levels of psychological development) as well as the macro-level (between opposing metaphysical ideologies).

5. Integration

a. Recognizing Conflict

Integration is a resolution of conflict, whether internal or external, that first requires a recognition of that conflict. Conflicts are created by systems having incompatible goals (or incompatible processes needed to maintain themselves). The same goals then recur regardless of changing conditions that block those goals, and in humans this takes the form of recurring feedback loops that conflict with more adaptive motives. The corpus callosum then allows us to repress, also producing other absolutizing phenomena. To integrate we then need to acknowledge differing desires over time and stop them hijacking our processes.

b. Reframing

A frame consists of limiting assumptions that focus our attention on one thing rather than another. Even the most basic framing does not have to be seen metaphysically, as it can be questioned. Reframing is prompted by frustration created by conflict, making it possible (with optionality) to switch to a wider frame free of the conflicts of the previous one. We are always obliged to expand frames rather than being able to free ourselves of them – an error-led process of responding imperfectly to integrate conflict rather than deduction from a frameless position.

c. Responses to Intractability

Conflicts may be intractable because at least one side lacks motive or perhaps capacity to resolve them. At times practical situations require the use of power to impose our will, which can be justified by greater integration of judgement, but this should not be used as a shortcut. Intractable conflict can be addressed by using an array of different types of context, often in combination through practices that use them. These contexts may be locked together, but opening up one of them can breach the absolutizing of the conflict.

d. Integration of Desire, Meaning and Belief

A division into the three levels of desire, meaning and belief offers a helpful practical analysis of integration, though these levels are highly interdependent. Integration of desire occurs when the energies previously directed towards incompatible goals are united. The bodily context of mindfulness enables this temporarily. Integration of meaning is the unification of a previously fragmented associative response to symbols, developing understanding in both of the interdependent ‘cognitive’ and ‘emotive’ senses. This enables the integration of belief, in which previously opposed beliefs become mutually acceptable, and thus the absolutization that divided them is overcome in the long term.

e. Individual and Group Integration

The integration of individuals nests within that of groups, interdependent but differing in complexity. Both are subject to conflict and integration, with the representations causing conflict in groups being an aggregation of those of individuals. Formal or informal agreements create group beliefs that can be imposed or integrated, creating two kinds of peace: pax and shalom. Pax is superficial and temporary, but idealized shalom can also be disruptive, so both kinds of integration need to interact.

f. Temporary Integration

Temporary integration is a bodily state that abates absolutization and conflict only for as long as it lasts. This is not just a state of suppressive concentration, but rather one in which conflicts are contextualized due to relaxation, as in the Buddhist jhanas. However, temporary integration does not change the long-term neural tracks of belief, which will require a critical thinking and judgement process. States of temporary integration need to be invested effectively to support long-term integration, but instead they can be easily reified and absolutized.

g. Asymmetrical Integration

The process of integration is evidently not simply a single-track escalator from messy conflict to a completely unified character, but is subject to contextually-dependent asymmetries. Our virtues mark a positive degree of integration linked to a context, but are only incrementally unified through a process of working on our weaknesses. A concept of asymmetry is important when discussing integration, to avoid projecting someone’s integration into a basis of unconditional authority (falling into a ‘guru trap’), and to prompt us to focus more on specific judgement rather than character as a more reliable locus of integration.

6. Practice

a. The Middle Way as a Framework of Practice

The practices discussed in this section of the book all contribute to an effective long-term response to absolutization. All need to be shaped by the five principles. The Middle Way as a whole provides an account of why these practices are beneficial and how they inter-relate. It can also become a ready basis for archetypal symbolism to inspire our practice. The Threefold Practice is a taxonomy for Middle Way practices based on the levels of integration (desire meaning and belief) in connection with whether they operate at individual or socio-political level.

b. The Threefold Practice

The Threefold Practice structure models the interaction of practices in a similar fashion to the Buddhist Threefold and Eightfold Paths, except that it takes more account of meaning, and is based on an incremental integration model, rather than a discontinuous enlightenment model. This makes it more compatible with support from scientific and systemic sources. The ways that all the practices address conflict should become clearer if we think of them in relation to all the five principles.

c. Individual Integration of Desire Practices

Individual integration of desire practices work on reducing the immediate press of conflict in our experience. This can be initially through ethical observance focused on dealing with major conditions that produce conflict, such as addiction. Some everyday practices, such as ordinary recreation, help to prepare the ground by reducing the stress of inner conflict to some degree. Bodywork, mindfulness and psychotherapy, however, provide much more direct and focused methods for reducing conflicts of desire in immediate individual experience.

d. Socio-political integration of Desire Practices

Socio-political integration of desire practices are closely interdependent with integration of meaning and belief too, but primarily focused on reconciling interests. Mediation techniques resolve conflict directly, whilst provisional discussion extends the conditions for mediation more broadly and can even be applied in political campaigning. An ethical avoidance of violence removes an immediate disinhibition and entrenchment of conflict, while the positive practices of care and friendship develop relationships that can provide the conditions for integrating conflicts, both internal and external. Active listening and volunteering also provide some specific practices that can support these conditions.

e. Individual Integration of Meaning Practices

Integration of meaning practices help us both extend our ‘cognitive’ range of symbols and our ‘emotive’ engagement with those symbols, to overcome fragmentation – gaps of understanding. The beauty of meaning and archetypal beauty found in the arts can help to do this, as well as developing integration of desire through aesthetic beauty and integration of belief through concepts. Focusing practice, loving-kindness meditation, and exploratory discussion can all also help to integrate meaning. Travel can be integrative as long as it actually extends experience, whilst learning foreign languages (and learning in general) help to integrate meaning more at the ‘cognitive’ end of the spectrum. Humour helps to integrate meaning through ambiguity, as long as we ‘get the joke’.

f. Socio-political Integration of Meaning Practices

Meaning is integrated at the shared socio-political level through communication in which all participants share sufficient of the meaning of symbols being employed. Ethical failings in communication, like lying, disrupt that shared meaning. Ritual also depends for its communal integrative effects on shared meaning, which needs to be ensured by ritual leaders rather than relying on representationalist assumptions. Longer term integration of meaning practice is supported by education in the arts, and by meaningful education in general taking embodiment into account. The further conditions for these require political support, and politics itself also requires meaning integration.

g. Individual integration of Belief Practices

Integration of belief is the process of making conflicting beliefs compatible by reframing. The process of reframing thought and feeling can be described as critical thinking, of which only one element is reasoning, but which also requires justification from experience, recognizing context, avoiding biases and fallacies, interpretation and credibility assessment – all of which are processes of contextualization rather than reasoning. Critical thinking skills can be practised in the context of any academic discipline, as long as the discipline does not constrain the assumptions that can be questioned (which in practice it often does). Cognitive behavioural therapy, reflection practice, and autobiography also provide further kinds of contexts where critical thinking skills can be used but should not be constrained.

g. Socio-political Integration of Belief Practices

Socio-political integration of belief practice helps to create the conditions for individual integration of belief practice through communication. The media, education, politics and academic activity provide obvious channels where critical dialogue can be created. However, the creation of genuine critical dialogue is always in tension with other social or economic priorities, so the cutting edge of the practice lies in finding the Middle Way, to enable that dialogue without destroying the conditions that allow it. I also see the development of Middle Way Philosophy itself as a socio-political integration of belief practice helping to support the conditions for integration through understanding.